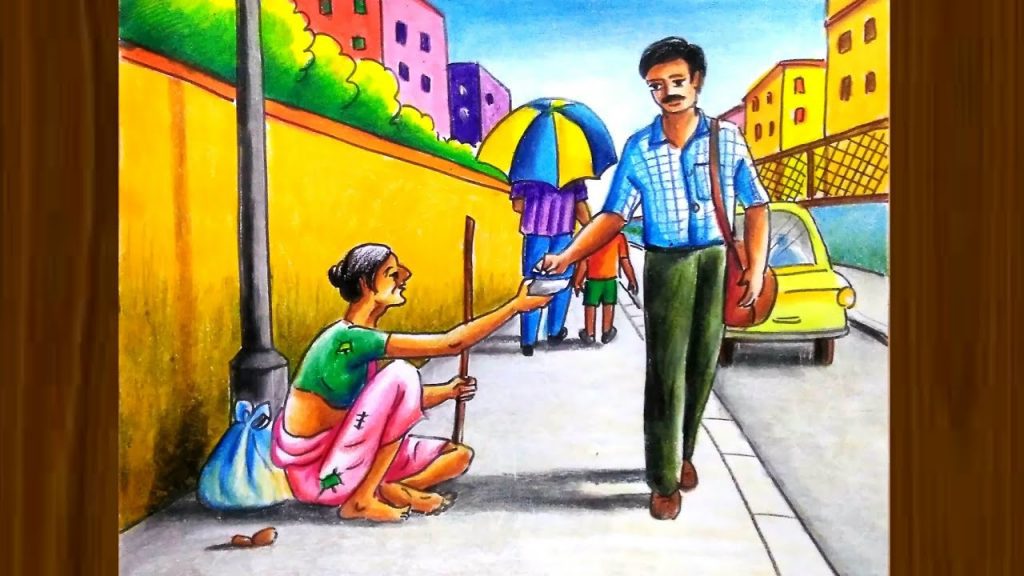

Have you ever come across a moment at a traffic signal, railway station, bus stand, or even on a road that pregnant woman coming with a child or a little boy with a running nose banging your car window, or a handicapped old woman or man asking you for alms? You can find these people everywhere in India where there is a regular crowd. And we always tend to give some coins or money to them. at times, out of sheer pity, fear of getting cursed by God, or frustration we tend to give them money. Beggar or Beggary is one of the most serious social and legal issues in India.

Another issue in India is vagrancy which occurs when an individual chooses to be unemployed. The term vagrancy means wandering which is a person who wanders from one place to another place without visible means of support. Vagrancy includes theft, gambling, contact with prostitution, etc. but the laws for vagrancy are not well defined in India for example prostitutes will be punished under the Prostitution Act and the person who commits gambling is punished under the Gambling Act.

The laws for begging and vagrancy differ from state to state. Several states criminalized begging and vagrancy. Especially this pandemic has caused a vulnerable impact on people living below the poverty line, many people lost their jobs and were driven to the streets for begging. This manuscript reviews the laws of vagrancy and beggar. The law criminalizes begging while the apex court says begging cannot be criminalized. Hence, In this article let’s understand why courts always go against the law when it comes to begging.

The Beggar and Vagrancy Numbers

On March 2021, Minister for Social Justice Thaawar Chand Gehlot gave us the number of beggar, aggregate, and by the state in a response to a query raised by the Indian parliament. A total of 4,13,670 beggars—2,21,673 men and 1,91,997 females—live in India. West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan are the states with the most beggar. As a result, the number of beggars should be divided by the state’s or Union territory’s population to make data comparable. If this is done, West Bengal and Assam would have the highest number of beggar. Northeast (excluding Assam), Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Himachal Pradesh have the fewest beggars.

The data is old and are from Census 2011, and a similar question (with identical numbers reported) was answered in Parliament in February 2015. However, one must be cautious. These are the census figures for both beggars and vagrants, not only for beggars. What is the distinction? The term “beggar” does not appear in the Constitution’s Seventh Schedule, unless “relief of the disabled and unemployable” is included in the state list. ‘Vagrant,’ unlike ‘beggar,’ is named in the Constitution. The concurrent list mentions “vagrancy, nomadic, and migratory tribes.” That is why the census not only counts the number of beggars but also counts the crippled and vagrants separately. According to the census enumerators’ instructions, beggars and vagrants are those who are not working in an economically productive capacity.

A look into the Beggar and Vagrancy Laws in India

The begging is not penalized under central law in India. The anti-begging laws exist in 22 states including union territories in India. The act that being as a derivative figure for all states is Bombay’s Prevention of Begging Act, 1959.

We all know the social definition of begging let us under the meaning of the word “Begging”. The Bombay Prevention of Begging Act of 1959 (hereinafter referred to as “the Act”) has defined the term “Begging” in Section 2(i) of the Act as”

- Soliciting or receiving alms, in a public place whether or not under any pretense such as singing, dancing, fortune-telling, performing, or offering any article for sale;

- entering on any private premises to solicit or receive alms;

- exposing or exhibiting, with the object of obtaining or extorting alms, any sore, wound injury, deformity of diseases whether of a human being or animal;

- having no visible means of subsistence and wandering, about or remaining in any public place in such condition or manner, as makes it likely that the person doing so exists soliciting or receiving alms;

- allowing oneself to be used as an exhibit to solicit or receive alms;

but does not include soliciting or receiving money or food or given for a purpose authorizes by any law, or authorized in the manner prescribed by [the Deputy Commissioner or such other officer as being specified on this behalf by the Chief Commissioner]”

Punishment can be anywhere between 1 to 3 years. But, if the court is satisfied with the circumstances of the case that the person found to be a beggar is not likely to beg again, the court might release the beggar on his assurance of abstinence from begging and being of good behavior.

Bengal Vagrancy Act and Cochin Vagrancy Act

Laws criminalizing vagrancy exist at the state level. In West Bengal, the Bengal Vagrancy Act, 1943, Section 2(9), defines a “vagrant” as “a person found asking for alms in any public place, or wandering about or remaining in any public place in such condition or manner as makes it likely that such person exists by asking for alms but does not include a person collecting money or asking for food or gifts for a prescribed purpose” and cochin as a similar provision.

Power of Police to arrest Beggar and Vagrants in India

The power to arrest a beggar only if he is found begging inside a private property can be arrested on a formal complaint by the owner of the property provided Under Section 9 of the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Beggary Act, 1975 which reads as follow, “Any police officer may arrest without warrant any person who is found begging and shall take or send the person so arrested to a Court: Provided that no person entering upon any private premises to solicit or receive alms shall be arrested or shall be liable to any proceedings under this Act except upon an oral or written complaint to such police office by any occupier of the premises.”

Note: If the court finds that the person accused was not involved in begging activities he is to be released. If the court is convinced that the person accused was involved in begging, the appropriate punishment will be given by the court.

To arrest a vagrant, under Section 16 of the Calcutta Suburban Police Act, 1866 provides that “ a police officer may arrest without a warrant “any reputed thief found, between sunset and sunrise, onboard any vessel or boat, or lying or loitering in any Bazar, street, yard, thoroughfare or another place, who shall not give a satisfactory account of himself; any person found, between sunset and sunrise, having his face covered or heavily disguised, to commit any such offenses as aforesaid.” Any such person may be imprisoned, with or without hard labor, for a term not exceeding three months. However, Section 4A(k) of the Act states that in dealing with women and children, the police must act “with strict regard to decency and with reasonable gentleness.”

The provisions of Sections 50, 51, 52, 56, and 57 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 shall, so far as may be, apply to every arrest under this Section, and the officer-in-charge of the police station shall cause the arrested person to be kept in the prescribed manner until he can be brought before a Court.

The Constitutional Aspect

All laws must be constitutional and the laws which violate the provisions of the Indian Constitution are void. Everyone is provided with the right to protect the socio-economic and livelihood in India. Article 21 of the Constitution of India provides rights to life and personal liberty which includes the right to live with dignity and livelihood. In the case of Bandhua Mukti Morcha vs. Union of India (1984) SC 802, it was held that right to live with human dignity, which is to be from the exploitative condition. In the case of Olga Tellis Vs. Bombay Municipal Corporation, AIR (1986) SC (180), the Hon’ble apex court held that the expression of life under Article 21 includes the right to livelihood. Article 23 of the Indian Constitution was incorporated to stop beggary and various other forms of Human Trafficking.

Is Beggary a Crime in India?

In 2018, the Delhi High Court in the case of Harsh Mander & Anr vs. UOI and Ors. held that criminalizing begging violates the fundamental right and Honble Chief Justice Gita Mittal and Justice Hari Shankar wrote (in the 23-page) order “People beg on the streets not because they wish to, but because they need to. Begging is their last resort to subsistence.”

Decriminalising Beggary

The Persons in Destitution (Protection, Care, and Rehabilitation) Model Bill 2016 aims to offer a life of dignity to the beggar and homeless, and others who live in poverty or abandonment.

Under this bill, however, employing a kid for begging, as well as any type of organized, syndicate, or coerced begging, will be illegal and punishable under the Juvenile Justice Act and the Indian Penal Code, according to the draught law. Furthermore, anyone caught begging will be sent to a rehabilitation center, for which states have been asked to make budgetary provisions. The district welfare officer, department of social welfare, or state department in charge of destitute and beggary issues will be in charge of supervising, monitoring, and coordinating the implementation of this act in the districts. At the state level, the director of social welfare will be accountable.

The bill, on the other hand, is a model law that states must adopt and notify. Begging is also a non-bailable offense, meaning that the accused must apply to the court to be released from custody while the investigation is underway. In India, there is a low degree of knowledge about the availability of free legal assistance, and activists have frequently complained about the poor quality of such representation. A person accused of begging is unlikely to be able to afford legal representation, making bail extremely difficult to obtain.

Though the draft bill would not outright criminalize begging, it does enable persons who are caught begging regularly to be held permanently in rehabilitation centers with police aid, if required. Furthermore, the plan calls for the issuing of identity cards that might be used for monitoring. These rules may also allow and help the police in conducting raids and ‘clean-up drives,’ putting the situation in a similar scenario to what it is currently.

What about the Children forced to Beggary?

The West Bengal Slum Areas (Improvement and Clearance) Act, 1972 details the government’s extensive authority to improve and clear slums, which then naturally leads to vagrancy. Children are not expressly referenced or excluded. And State laws on begging vary significantly in how they punish minors who are discovered begging. Children discovered begging are considered victims in need of care and protection under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, and are handled by child welfare committees, but certain state laws treat them as offenders who can be transferred to an institution.

Conclusion

In light of the existing gaps in anti-beggary legislation, it is high time to introduce new legislation addressing the issue, either repealing or amending some of the existing provisions to implement a completely rehabilitative approach and changing the definitions provided in the Act, which appear to be very vague about terms like ‘wandering in public’ or ‘no visible means of subsistence,’ and removing the issue from its ambit.