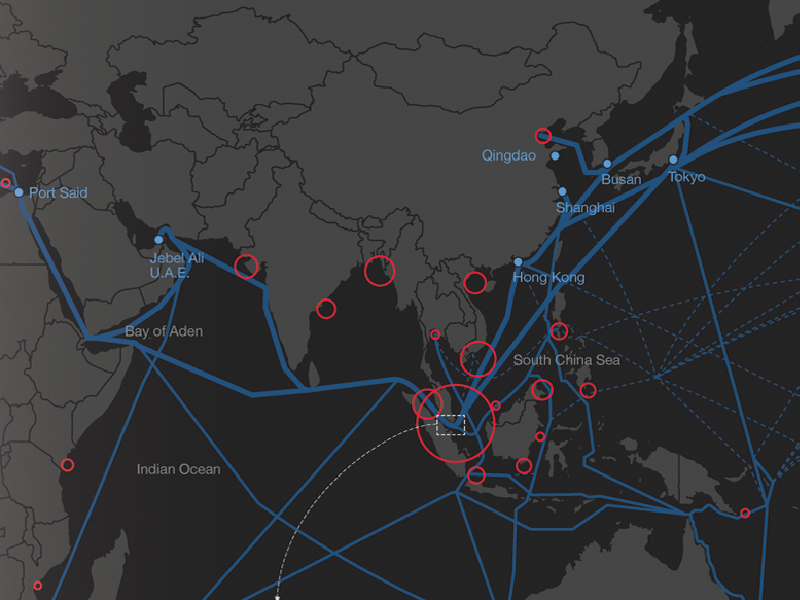

The constant expansion of global trade has necessitated a directly corresponding expansion of commodities transportation across the world’s huge oceans. The necessity to secure this flow of trade against seafaring pirates has long been acknowledged by the international community. Because of this, the recent dramatic increase in piracy has attracted a lot of international attention. Pirates chose their targets around the world based on regional factors. Piracy on the high seas has been suppressed for centuries thanks to rigorous international enforcement aided by a legal regime that was a model of international collaboration.

Today, as a long-simmering piracy problem erupts off the Horn of Africa, states have pleaded with the international community to refrain from enforcing the law against a gang of transnational criminals who threaten to halt much of international shipping. It’s especially difficult to reconcile the global abdication of prosecutorial responsibility with the haste with which the same countries have tried to prosecute far more complex and politically sensitive acts. The present study seeks to examine the violent acts that happened due to piracy, the laws and rules governing seas, and the role of international conventions in this regard. It will also be dealing with the law of sea rules on piracy and their inadequacy to cope with their violent activities.

Piracy under International Law

Piracy poses a threat to maritime security by jeopardizing the safety of sailors and the security of navigation and commerce. These illegal acts may result in the death of seafarers, physical harm or hostage-taking, substantial interruptions in commerce and navigation, financial losses to shipowners, increased insurance premiums and security costs, increased costs to consumers and producers, and environmental damage. Attacks by pirates can have far-reaching consequences, such as impeding humanitarian aid and raising the expense of future supplies to the impacted communities. In particular, Articles 100 to 107 and 110 of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provide the framework for piracy repression under international law.

The United Nations Security Council has repeatedly stated that international law, as embodied in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea of 10 December 1982 (‘The Convention’) establishes the legal framework for combating piracy and armed robbery at sea, as well as other ocean activities. In its resolutions on oceans and the law of the sea, the General Assembly has frequently urged States to work together to combat piracy and violent robbery at sea. The General Assembly, for example, highlighted “the critical importance of international collaboration at the global, regional, subregional, and bilateral levels in fighting, in conformity with international law, threats to marine security, including piracy” in its resolution 64/71 of 4 December 2009.

Codification on the Law of Seas concerning Piracy

Some of the old legislations on the law of seas concerning piracy are as follows:

- League of Nations (1926 )- The League of Nations made the first steps to codify the law of the sea. Experts for the Progressive Codification of International Law were chosen by the League of Nations Council. The Committee of Experts adopted a list of preliminary examination themes, including piracy, at its First Session in Geneva in April 1925, which lasted a week, and members of the Committee of Experts formed eleven sub-committees to report to the Committee of Experts on these issues. A year later, the committee sent questionnaires to the governments, including one on piracy, as well as a report on the topic and a tentative draught of a convention.

- Harvard research in international law draft on policy – The Harvard Research Program established a Committee to study the international law of “piracy” independently of the League and its Reporter’s work. Professor Joseph W. Bingham of Stanford University led the Harvard Research draft. This endeavor resulted in a full draft Convention on Piracy (with 19 articles) as well as commentaries (Harvard Draft).

- ILC Draft Articles and the 1958 Geneva Convention on the law of the Sea – In its inaugural session in 1949, the International Law Commission (“ILC”) selected a provisional list of issues for which codification was deemed required and possible. This was the first serious attempt to codify piracy as a criminal offense under international law. The new high seas regime was examined and eventually included in what was then known as piracy in international law during the seventh and eighth sessions of the International Law Commission. In 1956, the ILC completed its work by adopting Articles on the Law of the Sea with Commentaries, known as the “ILC Draft.” Articles 38 to 45 of the draught set forth the provisions for piracy. In their draught of the Convention, the ILC first defined piracy in Article 39.

Modern regulations on the law of seas concerning piracy are as follows:

- Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), 1982

UNCLOS is the foundation of current maritime law, and it is even referred to as the “Constitution of the Oceans” by some. The convention went into force on November 16, 1994, after work on the draught began on December 10, 1982. The UNCLOS makes it plain and necessary that an act must be illegal in order to be classified as piracy, but it does not specify whether it must be prohibited under domestic or international law.

Article 101 of UNCLOS defines piracy as:

- Any illegal acts of violence or detention, or any act of depredation, undertaken for private goals by the crew or passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft, and directed by the crew or passengers of a private ship or a private aircraft.

- At sea, against another ship or aircraft, or against people or property on board such a ship or aircraft.

- Against a ship, aircraft, persons, or property in a location outside of any State’s authority.

- Any voluntary participation in the operation of a ship or aircraft with knowledge of facts qualifies the ship or aircraft as a pirate ship or aircraft.

Incidents of Piracy

The fact that piracy is subject to universal jurisdiction is one of the most indisputable features of international pirate law. Any state may lawfully prosecute a pirate, even if the state has no connection to the pirate’s acts. They are, after all, the enemies of humanity. Despite the rule against piracy, international law does not recognize piracy as a substantive crime.

In view of current events and the acts of those States that have caught pirates, the tenor of Article 105 takes on greater significance. The Alondra Rainbow incident and prosecutions provide a famous illustration of the universality principle in regard to piracy. The Alondra Rainbow was a Japanese tanker with a Filipino crew and two Japanese officers in command. The tanker was on its way from Indonesia to Japan when it was boarded by pirates. The pirates were later apprehended by the Indian Navy, who brought the ship back to India. An Indian court tried and convicted the pirates. Similarly, the US and the UK have established a pattern of transporting pirates arrested in the Gulf of Aden to Kenya for trial, despite the fact that Kenya is rarely involved in the incidents. Kenya asserts its universal jurisdiction as a signatory to the UNCLOS.

In 1985, several members of the Palestine Liberation Front (PLF), a branch of the Palestine Liberation Organization, boarded the Achille Lauro, an Italian flag cruise ship heading from Alexandria to Port Said (PLO). One of the passengers was slain by the hijackers. Because of the hijackers’ alleged political intentions and the absence of a second ship or vessel, some regarded the hijacking as piracy, while others did not. The ostensible loopholes, combined with the glaring reality of the Achille Lauro incident, prompted Italy, with the backing of Austria and Egypt, to address a convention to combat maritime terrorism.

Modern piracy has amassed an alarmingly dangerous amount of currency, and it is no more a subject of antiquity or historical interest. The current international regime on the matter isn’t completely inadequate. However, there are two significant recommendations that have been made.

First, a more forceful UN Security Council response will address the urgency of the crisis and, at the very least, halt the situation by deterring pirates. Second, combining the international definition and prohibition of piracy with a real judicial process, preferably inside the frameworks of the international criminal court, will provide a longer-term and more durable solution.

Conclusion

It can be concluded that piracy has been a persistent problem for thousands of years, for as long as ships have sailed the oceans and as long as states have conducted maritime trade. It has been characterized by treaties and customary international law. These norms and regulations are quite old when it comes to piracy. And we’ll stick to piracy in the sense of waylaying or otherwise interfering with ships, as opposed to piracy in the sense of unlawful use of someone’s produce or idea, which is another definition of piracy. Even now, it is widely acknowledged that these definitions of piracy continue to offer legal and practical obstacles in the battle against piracy in the modern world.

The key issues include, first, the fact that piracy jure gentium cannot be committed in the territorial sea/internal waters under present rules, as it relates to issues of coastal state sovereignty. Second, the phrase “private ends” should be understood objectively; as a result of this action, political and terrorist acts undertaken on the high seas may qualify as piratical in nature, even though the piracy clauses in the provisions must be construed as a subsidiary in nature. Modifications to the current law should be made to establish a legal foundation for punishing these illegal conducts as well.