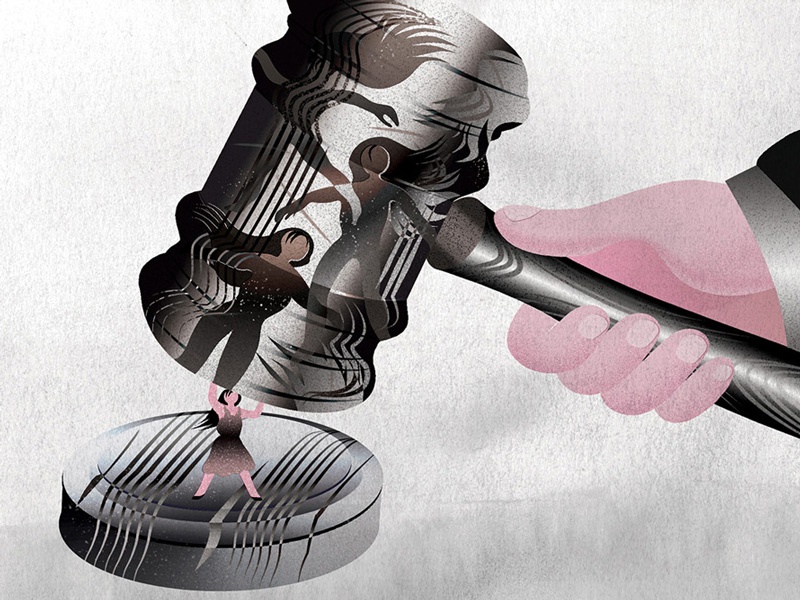

The category of sexual offenses includes non-consensual sexual acts like rape, harassment, assault, and other types of sexual harassment. They form a substantial part of the total percentage of crimes committed and attract fairly high public attention. Such sexual offenses in people’s eyes bear evidence of society’s actual moral degradation. As a result, both the victim and the defendant of sexual offenses form a distinct category than the ones of normal offenses. The victim and the perpetrator of the offense are made to undergo social scrutiny once they are caught by the public eye.

Due to such reasons, various segments of our population have been advocating the use of anonymity in such sexual offenses. But these advocates are divided majorly into two camps, i.e. one vouching for the victims and another for the defendants. There has been a protracted debate on the same and we have made certain progress. But the scale of progress is not the same for both these camps.

Protecting Victim’s Identity in Sexual Harassment Cases

In a plethora of judgments, courts have reiterated the fact that sexual offenses like rape are beyond the physical act of ‘sex’. It is a breach of not only someone’s body but someone’s soul and dignity. A victim is scarred for life. It was held in Shri Bodhisattwa Gautam vs. Miss Subhra Chakraborty, “Rape destroys the entire psychology of a woman and pushes her into a deep emotional crisis. It is only by her sheer willpower that she rehabilitates herself in the society which, on coming to know of the rape, looks down upon her in derision and contempt. Rape is, therefore, the most hated crime.” Therefore, it deprives the victim of her most cherished Right to life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution.

Very often a victim of rape is ridiculed and looked at with contempt as she is the one who is often labeled as the “abettor of the crime”. Rooted in the orthodox patriarchal beliefs of our society, our society’s mindset generally shifts the blame on the victim. She is publically shamed and has to undergo extreme hardships. Usually, it also jeopardizes her marriage prospects and employment opportunities. All of this makes her rehabilitation back into society an uphill battle. The victim not only has to deal with the scars of the crime but also the ones society inflicts after the crime. The same contention was upheld by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in the case of Nipun Saxena vs. Union of India. It was observed by the apex court, “A victim of rape will find it difficult to get a job, get married, or get reintegrated in the society like a normal human being”.

As our society treats such a victim as an “untouchable” and a “pariah”, it has been contended that protecting the victim’s identity should be the law’s primary duty. Thus, Section 228A was inserted in the Indian Penal Code by Criminal Law Amendment Act, 1983. It prescribes that the identity of a rape victim must be kept hidden. Additionally, the offense has been made non-compoundable so as to prevent giant media houses from buying victims’ consent by money power. Also, Section 23 of the POCSO Act, 2012 prohibits the disclosure of name, address, photo, family details, school, neighborhood, or any other particulars which may lead to the disclosure of the identity of a victim of sexual harassment. Moreover, in the case Om Prakash vs. State of Uttar Pradesh, the Hon’ble SC criticized even the disclosing of the victim’s name in the judgment and emphasized against it.

However, the critics have questioned the objective behind hiding the victim’s identity. They argue that it stems from the orthodox belief that the victim is somewhere to be blamed for the offense committed against her. Hiding it would be tantamount to reinstating the social stigma that is attached to the victim. It is contended that revealing her identity would be useful as the victim would become a symbol of protest. In fact, the mother of the 2012 Delhi gang-rape victim herself came forward to reveal her identity as she wanted her daughter to become a symbol of strength for other girls and that she wanted to fight not only for her daughter but many like her. It is also believed that making complainants anonymous would increase the likelihood of false complaints of sexual harassment being filed.

Despite these arguments, it has been found that making a victim’s identity anonymous serves more purpose than revealing. Many families are reluctant to come forward and file complaints due to the fear of bad reputation and embarrassment in society. Making them anonymous would save them from this ordeal and encourage them to seek justice.

Protecting the Defendant’s Identity in Sexual Harassment Cases

In the year 2019, the Youth Bar Association filed a petition in the apex court seeking extension of the anonymity principle to the defendants as well. The petitioners claimed that under Vishakha guidelines issued by the honorable court, anonymity was granted to the victim to safeguard her integrity and dignity but the accused was not granted any such protection. The petitioners argued that the accused should have the same protection to secure his rights as well. Making the identity of the accused public would violate his right to life and personal dignity safeguarded by Article 21. The petition also pleaded that some guidelines must also be issued to the media directing them not to disclose the identity of the accused till the culmination of the investigation. As a result, the SC bench, headed by Justice S.A. Bobde issued a notice to the Central government seeking their view on this plea asking for protecting the identity, integrity, and reputation of the people accused in cases of sexual harassment, at least till the completion of investigation in such cases.

Currently, there is no such safeguard put in place for the defendants in India. However, Section 21 of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act protects the identity of alleged rapists who are below the age of 18 years.

There is a lot of debate surrounding this issue. It is argued that disclosing the identity would do the same amount of harm to the victim and the accused. It breaches privacy and does irreparable harm to the victim and accused identity equally. It will harm the accused even beyond the crime. In times like these where media frenzy is at its peak the amount of psychological damage that revealing the identity of the accused can do goes beyond our imagination.

And in serious sexual harassment, a person will be tagged as an offender in the public eyes even when he is acquitted. The loss of reputation and dignity can never be compensated. Such contempt drives many innocent people falsely charged with such offenses to commit suicides, seeing this as the only way to get out of this shame of being labeled as a sexual offender. After the accused is exonerated by the court of law, people still see him as an offender, following the principle of “no smoke without fire”. In fact, it not only affects the accused but his entire family. His whole family has to bear the embarrassment and shame.

In English law, the identity of the accused was made anonymous along with the victims in the 1970s. However, it was later abolished in 1988. It was believed that there was no pertinent reason to grant special protection to a sexual offender. Hiding the identity of the accused would convey the wrong message that such complaints are less reliable. It was also contended that such a law would prevent other victims of the same offender from coming forward and securing the prosecution.

And this way the debate goes on. But before any concrete step is taken, it is important that certain points need to be kept in mind. The necessity of empirical evidence cannot be neglected. Ground study on the impact of disclosing the identity of the accused has on him, his family, and the case needs to be conducted to bring about a sound policy.

Striking a Balance – Concluding the Discussion

In several instances, our courts have emphasized the need of protecting the victim’s identity. The harm of revealing her identity can be unequivocally acknowledged, no matter what the critics claim. It does seem reasonable to do so. Sexual harassment has an inherent stigma attached to them that can have a devastating effect on the victim’s life. But not acknowledging the same effect that the revelation can have on the defendant is injustice. In several cases where the accused is acquitted, he is not able to reintegrate himself into society as a normal person. It can do an equal amount of harm for both the victim and the accused.

Nonetheless, the arguments against the protection also seem to hold some substance. This leads us to the conclusion that blanket protection awarded to the accused might not seem plausible. This can do more harm than good. However, what seems plausible is partial protection, i.e. protection until the investigation is completed or until the final judgment is pronounced. Considering the reach of mass media, bringing this change becomes very pertinent. As we march towards a bright and equal future, striking a balance between the rights of the victims and the defendants is the need of the hour to strengthen the principles of justice and equity.