Traditional knowledge is the term used to describe the wisdom, techniques, and norms which are passed down through a culture from one generation to the next. It includes a wide range of disciplines, such as farming, pharmacy, and craftsmanship, as well as other cultural traditions. To maintain culture and traditions and foster innovation across a variety of disciplines, traditional knowledge is crucial. Unfortunately, it frequently faces the possibility of being misused, exploited, or seized by others without just reward or acknowledgment. By offering legal immunity to the producers and holders of traditional knowledge, patent laws have an essential function in preserving it.

With an emphasis on Indian traditional activities like Ayurveda, textile production, and crucial handwork, this research study examines the importance of patent laws in safeguarding traditional knowledge. Using patents as an example, individual inventors are protected for their unique ideas, while collective knowledge that was developed over many generations by a group of people is sometimes not only left unprotected but even in danger from patents. The global system of protecting knowledge is largely unbalanced: while many intellectual property laws are available for the protection of (individual) novel innovations and other mental achievements, little protection is given for traditional (collective) knowledge, which was frequently developed over centuries through oral tradition.

Much data points to the urgent necessity to close this legal loophole and give traditional and indigenous knowledge the proper legal protection. First, a sizable portion of valuable but threatened resources are under the sovereignty of indigenous people. Indigenous populations’ ecological knowledge is more important than previously believed (both qualitatively as well as quantitatively), and as a result, it can help maintain such treasures. In addition, a quarter of the population globally still relies on traditional treatment, not solely due to tradition but also out of (financial) necessity. Traditional knowledge is essential to ensuring global food security and health. Last but not least, in addition to these pragmatic goals, the topic of traditional knowledge protection is necessary from the perspectives of legal pluralism, socio-legal justice theories, and psychological justice theories. In establishing legal immunity for traditional knowledge, several initial issues must be resolved (e.g. ownership of the rights, policy objectives, acquisition, etc.).

Looking into the Background

India has a long history of ways of knowing which have grown over time. For instance, India has used the ancient medical system known as Ayurveda for many centuries. The elaborate styles and methods used in Indian fabric production, such as block printing, embroidery, and weaving, have also received praise. Another crucial area where Indian traditional expertise is prized is woodcarving and pottery making.

Unfortunately, the misuse and exploitation of traditional knowledge by outsiders have occurred frequently, making its conservation difficult. In recent years, there has been a rising understanding of the necessity of safeguarding traditional knowledge in order to foster innovation and progress as well as the preservation of cultural legacy. The Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL) and the Traditional Knowledge Resource Classification (TKRC) system are just two of the steps the Indian government has implemented to conserve cultural traditions.

Preserving Traditional Knowledge

Traditional knowledge must be protected in order to preserve the cultural legacy and foster creativity across a range of industries. By offering legal immunity to the creators and owners of traditional knowledge, patent laws play a critical role in preserving it. With an emphasis on Indian traditional activities including Ayurveda, fabric work, and critical craftsmanship, this paper seeks to investigate the function of patent laws in conserving traditional knowledge. The cultural dimensions of traditional knowledge protection are examined in the paper, together with the potential and difficulties presented by the use of patent laws.

The study makes the case that safeguarding traditional knowledge requires a sensible strategy that takes into account the interests of both communities and inventors. The article also emphasizes the significance of active citizenship in traditional knowledge protection and the requirement for an efficient legal system that guarantees just remuneration and acknowledgment for traditional knowledge holders. By giving its creators and holders legal protection, patent laws play a critical part in preserving traditional knowledge. By giving the creator temporary monopoly rights, the patent system aims to promote invention and creativity. A patent grant gives the inventor a legal monopoly over their invention, allowing them to stop others from producing, utilizing, or commercializing it without their consent.

Traditional knowledge can be shielded from theft and abuse by outsiders through the application of patent laws. Traditional knowledge holders can assert ownership and defend their intellectual property rights thanks to the legal framework that the patent system offers for the recognition and protection of traditional knowledge. The issuance of a patent also gives conventional knowledge owners the chance to profit from their expertise through the sale or licensing of their inventions.

Yet, there are several difficulties in applying patent laws to traditional knowledge. Since traditional knowledge is frequently shared communally within a group, it is challenging to pinpoint a single creator or owner. A high level of innovation and ingenuity, which may not be present in conventional knowledge processes, is also required by the patent system. The granting of a patent may also result in the commodification of traditional knowledge, which would result in its commercialization and eventual extinction. For a very long time, traditional (regional), especially indigenous understanding has only been given tangential importance. Recent times, however, have seen a growing association between traditional and indigenous knowledge and environmental and global goals of sustainable development, particularly biodiversity preservation. There is “great untapped potential for developing, disseminating and utilizing traditional knowledge of India,” according to the National Intellectual Property Rights or NIPR Policy, 2016.

Reaching out to the less prominent IP creators, such as the owners of Traditional Knowledge (TK), is crucial. Both the 2002 version of the AYUSH Policy and the 2016 draught favor promoting the Traditional Medicine sector. The National Health Policy of 2017 also aims to promote AYUSH systems on par with contemporary therapies.

A Socio-Legal Study into Indian Traditional Knowledge and Practices

India has a diverse cultural legacy that includes customs like Ayurveda, textile production, fine handicrafts, and many others. These customs have been passed down from one generation to the next and are now an essential component of the cultural character of India. But in today’s world, where modernization and globalization are endangering the survival of traditional customs, it is more crucial than ever to preserve these traditions.

Using patent law is one strategy to safeguard these customs. By giving them the only right to create, utilize, and commercialize their innovations for a set amount of time, patent law is a method of protecting inventors’ ideas. This protection encourages inventors to expend their time, energy, and resources.

Patent law can be utilized to protect the innovations and advancements made by the practitioners of traditional Indian practices including Ayurveda, fabric work, and important handwork. Ayurvedic practitioners who have created novel medications or therapies based on antiquated Ayurvedic concepts, for example, may employ patent law to safeguard their intellectual property rights. These practitioners can prevent others from stealing their ideas by giving them the only right to make use of and sell them.

Similar to how it can be used to protect designs and methods created by artisans who have spent years refining their craft, patent law can be utilized to protect crucial handwork and fabric work. These artists may avoid others copying their work and passing it off as their own by giving them the sole right to use and sell their designs.

The application of patent law in the context of conventional Indian traditions, however, is not without its difficulties. For instance, some contend that because it could result in the commodification of certain processes, patent law may not be appropriate for protecting traditional knowledge. This can lead to the commercialization of certain activities, which might diminish their significance and validity from a cultural perspective.

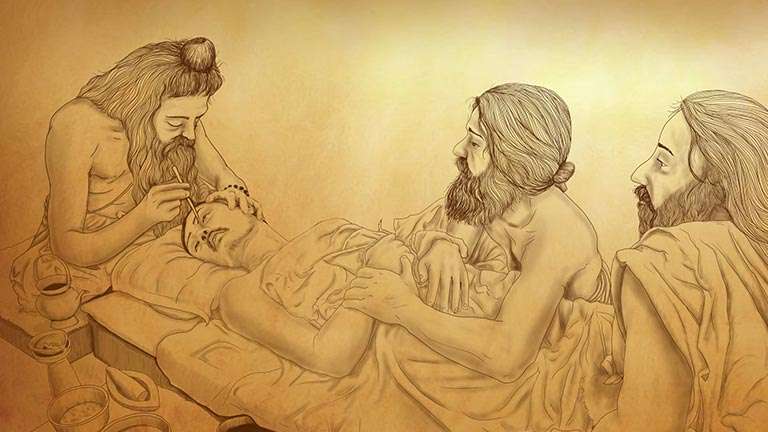

Ayurveda

A subcategory of traditional knowledge is what is typically referred to as traditional medicinal knowledge. It is made up of the therapeutic and restorative abilities of plants used in indigenous culture, including genetic resources. The basic features of traditional knowledge are frequently used to classify it: it is developed over a prolonged time frame and passed down from one generation to the next; new knowledge is integrated with the existing as it is improved; the improvement and creation of knowledge are collaborative efforts; and ownership of indigenous knowledge varies between indigenous peoples. It typically refers to medical knowledge created by indigenous cultures that combines spiritual treatments, manual techniques, and medicines derived from plants, animals, and minerals in order to treat illness or preserve welfare.

For its inventors as well as the global intellectual community at large, the connection between intellectual property rights and conventional medical knowledge has become inevitable. For self-sustainment, the economic well-being of knowledge holders, and competitive business advantage, it has become essential to preserve, safeguard, and promote traditional medical knowledge. In particular, for traditional medicine, the exponential increase of traditional knowledge has sparked new types of intellectual property rights protection. In the majority of the nation’s regions, the Indian Systems of Medicine (ayurveda, homeopathy, Unani, etc.) predominated as the primary and, in some locales, the only available systems of medicine.

Despite its popularity and broad use, there was no attempt made to develop a policy or law to safeguard the amount of intellectual property in the system. Traditional medical practices are not currently protected by patents, and pharmaceutical corporations frequently use this information in the creation of new, patented medications. Traditional knowledge is rightly disqualified from patent protection in the Western patent system. Additionally, it is impossible to reconcile intellectual property rights with indigenous peoples’ traditional beliefs. Pharmaceuticals and food goods are now covered by product patents thanks to changes made to the Patents Act in 2005.

Hence, if they satisfy the requirements for patentability, novel compositions and procedures in Ayurveda, Siddha, and Unani may be protected by patents. In fact, an Ayurvedic medicine called Jeevani, produced by the Tropical Botanical Garden and Research Institute in Thiruvananthapuram, received a new process patent even earlier. This case became well-known in the field of benefit sharing in traditional knowledge. There are many patents for various Ayurvedic, Siddha, and Unani formulations.

Neem

The neem tree’s botanical name is Azadirachta Indica, and it has been used for millennia in agriculture as an insect and pest repellant, veterinary medicine, cosmetics, and toiletries. It is mentioned in ancient Indian manuscripts dating back more than 2000 years.

The oil extracted from its seeds can be used to treat colds and flu as well as being blended with soap to treat skin conditions, malaria, and meningitis. Neem extracts can also be used to combat the hundreds of pests and fungal diseases that attack agricultural crops. 18 European Patent Office in 1994. A patent was given by the (EPO) to the W.R.

Grace Compan and the US Department of Agriculture for a technique using hydrophobic extracted Neem oil to combat fungus on plants. A coalition of foreign NGOs and Indian farmer representatives opposed the patent in court in 1995. They provided proof that Neem seed extracts’ fungicidal properties, which have been employed for generations in Indian agriculture to safeguard crops, are not patented. According to the evidence, all of the elements of the current claim were known to the public before the patent application, and the EPO decided in 1999 that the invention did not constitute an innovative step. The patent for Neem was canceled by the EPO in May 2000.

Turmeric

On March 28, 1995, Suman K. Das and Hari Har P. Cohly, two Indians living in the US, were issued US Patent 5,40,504 on the use of turmeric in wound healing. The University of Mississippi Medical Center in the United States received the patent. This patent made the novel discovery of administering an effective dose of turmeric orally and topically to speed up the healing of wounds. Prior to being awarded, a patent must satisfy the fundamental criteria of invention, non-obviousness, and usefulness. As a result, the patent is rendered invalid if the claims have been covered by the pertinent published 32 references found by CSIR, some of which were over a century old and were written in Sanskrit, Urdu, and Hindi, demonstrating that this discovery was well-known in India before.

On October 28, 1996, CSIR formally requested a re-examination of the patent with the USPTO. The examiner once more rejected all the allegations on November 20, 1997, citing their foreseeability and obviousness. The re-examination process was completed in this case on April 21, 1998, when the re-examination certificate was issued.

Protecting India’s Traditional Knowledge of Handloom and Handicraft Industry

For many years, India’s rural economy has been supported by the handloom and handicraft industries. After agriculture, it is one of the greatest employers in the nation and a major source of income for both the rural and urban populations. The industry is well known for being a pioneer of environmentally friendly zero-waste procedures and operates on a self-sustaining business model, with craftspeople frequently growing their own raw materials. India is home to 7 million craftspeople, according to official estimates.

Yet, information from unreliable sources suggests that there may be 200 million artisans worldwide. Due to this sector’s informal and unorganized nature, the range is broad and the number is disparate.

To maximize the sector’s potential, the government is actively striving to develop it. The difficulties that artisans encounter include the lack of funding, the low adoption of technology, the lack of market knowledge, and the weak institutional foundations for growth. The underlying contradiction of handmade goods, which are frequently at variance with the volume of manufacturing, is another problem plaguing the industry. The government has started a number of programs and initiatives to address these issues. Ambedkar Hastshilp Vikas Yojana, Mega Cluster Scheme, Marketing Support and Services Scheme, and Research and Development are a few examples of such programs. The Office of the Development Commissioner of Handicrafts, which is in charge of implementing the government’s National Handicraft Development Programme, is responsible for these programs.

India is an artistic and crafty country. Nearly every region has its own traditional art, which can take the shape of paintings, carvings, embroidery, saris, and more. We are incredibly fortunate to have been born in a nation with such rich diversity. Regrettably, several of these art forms are in danger of disappearing, Here are some of the most stunning ones that should be saved right now:

- Manjusha Art is thought to be the only kind of art in India that is shown in series, with each piece illustrating a different narrative. This style of art first appeared in Anga Pradesh (modern-day Bihar). Earlier, they primarily produced items to be used at the district of Bhagalpur’s annual Bishahari festival, a festival honoring the snake god. Under the British occupation of India, this art form blossomed ferociously. But, around the middle of the 20th century, it began to disappear. The Bihar government, fortunately, is working to resuscitate this trade and register it as Bhagalpur traditional art.

- Parsi embroidery has contributed to India’s rich textile history. This art form was created in Iran during the bronze period and over time included elements of European, Chinese, Persian, and Indian culture. Parsi Gara Saris, which take about 9 months to create, are saris that feature Parsi needlework. Yet, there are presently surprisingly few of these on the market. The dwindling Parsi population and the abundance of cheap, mass-produced clothing are the causes.

- There are currently just six living Roghan painters in India. Seven generations of the Khatri family have practiced the craft in the Kutch region of Rajasthan, but they worry that this will be the final generation to do so because the next isn’t as adept or experienced enough as they were. Castor oil, paints, and a 6-inch-thin metal rod are used to create this remarkable form of painting on fabric. The artworks are pricey, and most buyers are foreigners.

- 4) The priciest saris in the world are Patola Sarees, which feature some ikat embroidery. Each traditional Patola Saree can last for over 300 years while maintaining its color. The weaving of the saris takes around 25 days, and it takes four to six months to color the silk threads, which takes more than 70 days. The most expensive sari costs an astounding Rs 7 lakh. It takes at least 12 individuals more than two years to manufacture using supplies needed to make 27 ordinary Patola saris.

Conclusion

The socio-legal analysis of the preservation of Indian tradition through the use of patent law is a complicated and multidimensional topic. It is crucial to prevent the commodification or commercialization of traditional Indian practices, even though patent law can be a useful instrument for preserving the intellectual property rights of practitioners. We may safeguard these customs while simultaneously fostering innovation and development by employing a sophisticated and culturally considerate approach to the application of patent law.

References

- Dr. Gerard Bodeker, “Traditional Medical Knowledge, Intellectual Property Rights & Benefit Sharing” 11 Cardozo J. Int’l & Comp. L. 785 (2003).

- Anand Chaudhary & Neetu Singh, “Intellectual property rights and patents in perspective of Ayurveda” 33 AYU 20 (2012).

- Paul Kuruk, “Protecting Folklore Under Modern Intellectual Property Regimes: A Reappraisal of the Tensions Between Individual Rights and Communal Rights in Africa”, 48 American L. Rev. 769 (1999).

- Sachin Chaturvedi, “Kani Case”, A Report for Gen Benefit, available at www.uclan.ac.uk/genbenefit (Visited on February 13, 2019).