In a country that is thriving in politics, corruption has become almost synonymous with the system. Hence, it is imperative to constantly explore options as to how this corruption can be subdued and battled. Political corruption happens highly rampant in the country, and defection makes up a major part of this corruption. This article focuses on the concept of anti-defection law, its history, and development, and looks to answer whether these laws need to be stringent and if yes, then how?

What is Anti-Defection Law?

Defection in this context refers to the act of leaving or changing a political party to join the rivaling or opposite party. As was noted by a committee headed by Y.B. Chavan, a defector is defined as who is an elected member of the Legislature and had been allotted the reserved symbol of any political party. He can be said to have defected it, if after being elected as a member of either House of Parliament or a Legislative Council or Legislative Assembly of State or Union Territory and he voluntarily renounces allegiance or association with such political party provided that his action is not in consequence of the decision of the party concerned.

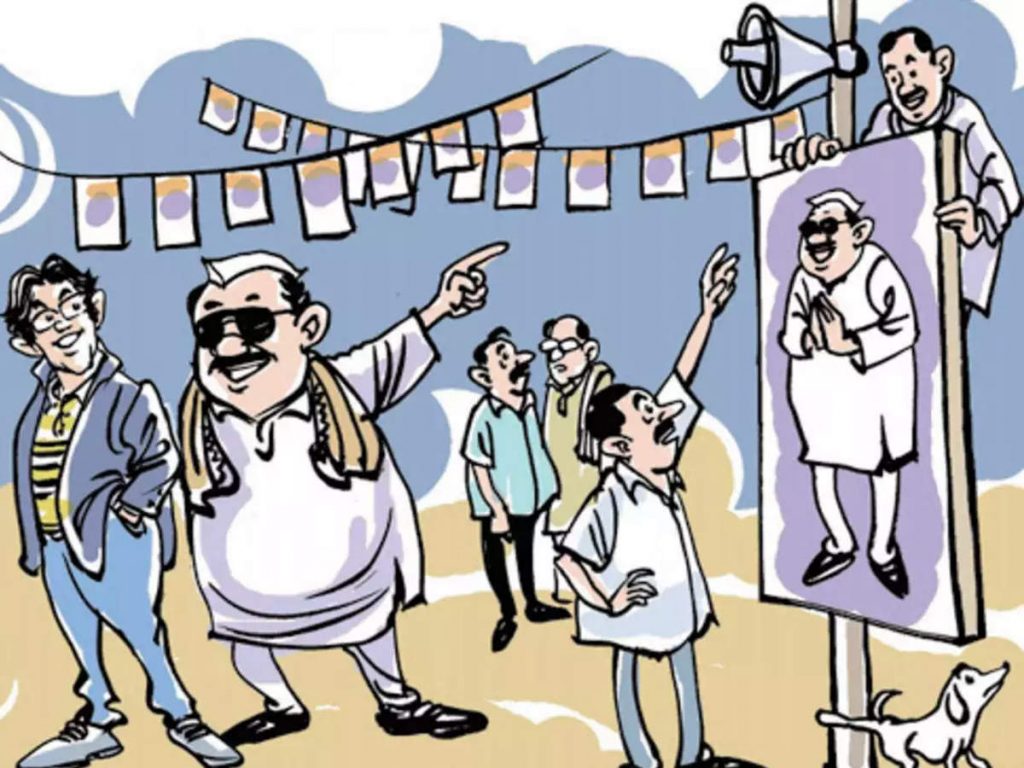

The problems which are ensured through defection can usually lead to an unstable system where there is constant fluctuation of party members and no clarity for the people to understand which party can they truly support and for what reasons, not to mention the horse-trading of legislators which does not sit well in a democratic setup like India. It enables party members to change their parties during an election for their personal benefit without giving thought to the effect it would have on the electoral system or the election.

The anti-defection law has been laid down in the 10th schedule of the Constitution of India and specifies the grounds on which a member of a political party can lose their position as an elected representative and further be disqualified from the party. The respective member shall lose their position of a Member of Parliament or Member of Legislative Assembly if they:

- Voluntarily give up the membership of a Party

- Vote or abstain from voting/ defy any Party whip

- Join any other Party

- Or, if an independent candidate joins a political party after the elections

Even though the following lay down the grounds for disqualification, the schedule also mentions a particular exception where a member would not be subject to the risk of elimination. In case of a merger between parties allowed by the law, provided that at least two-thirds of the legislators are in favor of the merger, the parties of the parties will not be subject to the risk of disqualification during the merger.

Criticism of the Anti-Defection Law

Anti-defection law, in its truest sense, avoids the instability of the system. It prevents the party members from solely looking out for their profits or benefits and puts into place a system that makes them accountable to the party they are a member of. It also facilitates mergers of political parties for the betterment of sections of the society, in comparison to defection where the prime beneficiary becomes the party member alone, leading to better decision-making in the system.

Even though the idea of anti-defection law is imperative, it has faced criticism over the years, along with the courts’ interpretations and precedents. Majorly, the critique that is raised against this law is on the lines of:

- It is against the essence of democracy

This stand is contended on three grounds, firstly that a democracy stands for representatives to put out what they believe the people stand for. Straight-jacketing members of a political party and giving them an ultimatum of disqualification if they do not support the actions of the party is not only curbing the rights of the members to express themselves but also takes away the space for discourse and discussion on a topic. Secondly, it takes away the power of legislators to hold the government accountable for their actions. The entire objective of voting in the parliament is to let the members express their opinions and standings concerning the issue in the debate, and if legislators do not have the power to choose for themselves, then voting just becomes an ineffective check on the government, and places much more power with the executives than the legislators. - It is not a mandatory law

Western developed countries do not see a need for anti-defection laws. Defections take place in these countries and there is no anti-defection law, yet the system seems to work without any major obstacle caused by the act of defection by the members. The legislators there, use this power to provide clarity to the people and to ensure that their beliefs are not compromised, which is the essence of democracy and the freedom of speech. In a country that is so politically and socially diverse, it is very hard to put everyone under a similar umbrella, which is why this law is against the representation of individualistic ideas.

Before delving further into the debate of whether this law needs stricter implementation, taking a look at the history of the development of this law is necessary to understand the context in which it was introduced and why it is important to raise the level of discourse about this issue in the current times.

When was it introduced in India?

The Anti-Defection Bill was proposed and passed unanimously, and after gaining assent from the President, came into force on 18th March 1985. The phrase Aaya Ram, Gaya Ram soared through the country in the last 1960s to 1980s as the number of defectors rose exponentially and political party members changed parties at a concerning rate. The phrase in itself developed during the first assembly elections in Haryana (1967) when an MLA Gaya Ram changed parties thrice within 24 hours after being elected. This was not the only case of switching ships, as was later seen with Bhajan Lal in 1980 when he shifted to Congress Party right after forming the Janata Party government.

In further studies, it was found that from 1967 to 1969, approximately 1500 party defections, and 313 individual candidate defections had taken place across the country. Furthermore, in the span of the next two years, by 1971, about 50% of the legislature had defected and changed parties and positions. It was during this time when Rajiv Gandhi proposed the Anti-Defection Bill, something which seemed necessary then.

The law has developed over time, and as it evolved, it has answered many ambiguities which might have arisen while applying this law. Starting with the case of Kihoto Hollohon v. Zachillu, the Supreme Court stated that the decision of the Speaker of the House, along with the Chairman would be legal and binding. The problem which arises from this statement is mostly the fact that there is no particular time frame set for the Speaker and Chairman to decide on the disqualification of a member. The Court in a succeeding case mentioned that the Speaker and Chairman would not be exempted from the process of judicial review as well.

The Supreme Court, in the case of G. Vishwanathan and Others v. Hon’ble Speaker Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly and Others, set down the precedent that voluntary resignation from membership could be either implied or explicit, and both would be considered valid. In case a member states that they have been wrongly disqualified as a defector, the burden of proof will lie on the member to show that their actions did not, in any manner imply their willingness to resign from the party. The grounds on which the Speaker could disqualify a member have also been laid down by the Supreme Court.

Another major case of defection was seen in Rajasthan where Sachin Pilot, the Deputy Chief Minister, and 18 other MLAs raised objections concerning Chief Minister Ashok Gehlot’s leadership, but they did not explicitly withdraw their support. Further instances like these have been cropping up across the country, which brings us to the question of what should be done about the anti-defection law, given that there are severe criticisms against it?

Implementation of the Law

Anti-defection law was put forward with the motive of curbing the horse-trading that goes on in the political arena, but over time it has been blatantly misused, and underused. The rules for politics seem to have very easily worked their way around this law for the use of the politicians, and the stability of the system has been compromised repeatedly. This leaves the people with two options, either to scrape off the anti-defection law and let the members shift parties as they please, or to put into place a more detailed and structural manner of this law. To do away with the anti-defection law would render the politics of the country into an even worse state, and any scope of exercising control over corruption would vanish.

Instead, what is needed now, is a better mechanism for the anti-defection law. Firstly, changing the authority who has the power to disqualify the members, and having a clear idea and guidelines on what grounds is the disqualification valid would help in reducing the ambiguity around the law. Secondly, the law needs to be used and applied rationally. It is to be taken into account that the law should not infringe someone’s right to self-expression but at the same time, it has to be ensured that there is a healthy discourse on an issue.

The law definitely requires stricter implementation, but that should not come at the cost of members being unable to voice their opinions. Apart from this, there has to be a system to ensure that members do not change parties with their whims and fancies whenever they find personal monetary or social benefit in doing so and instead work for larger representation of the people, not misuse this law.

Conclusion

The anti-defection law is to be studied thoroughly before making any changes, which would result in less exploitation and stringent application. The changes which are to be made have to be very detailed and thought out, any hurried decision in this field would be highly counterproductive.

Editor’s Note

The article extensively deals with the anti-defection law and the impact on the democracy of our country. It elaborates on the history and the development of this law and also looks over the judgments rendered by various courts upon the same issue. The article also deals with the criticism of this law and the idea of improving it to make India a better democracy.