The increase in orbital space debris is both a result of and a possible impediment to space activities. The dangers posed by debris dissemination in the most heavily used orbital regions illustrate the need to properly resolve the threats to space sustainability. The legal flaws in space debris remediation mechanisms stem from the fact that, while technological principles for debris removal and on-orbit servicing have been established, the legal structure for space activities does not enforce any legal obligations. Nonetheless, a review of the current legal framework reveals that there is a legal basis for the security of the outer space climate, which can be substantiated in more specific terms by the formulation of voluntary, non-binding instruments and incorporated in national legislation, as has already been done with space debris mitigation guidelines.

Introduction

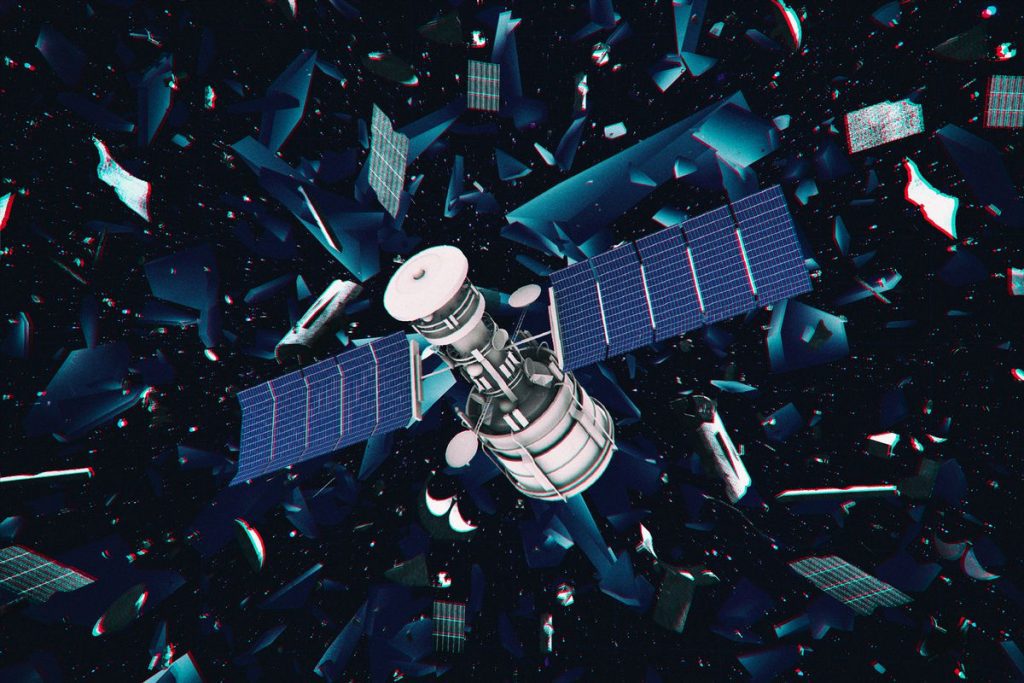

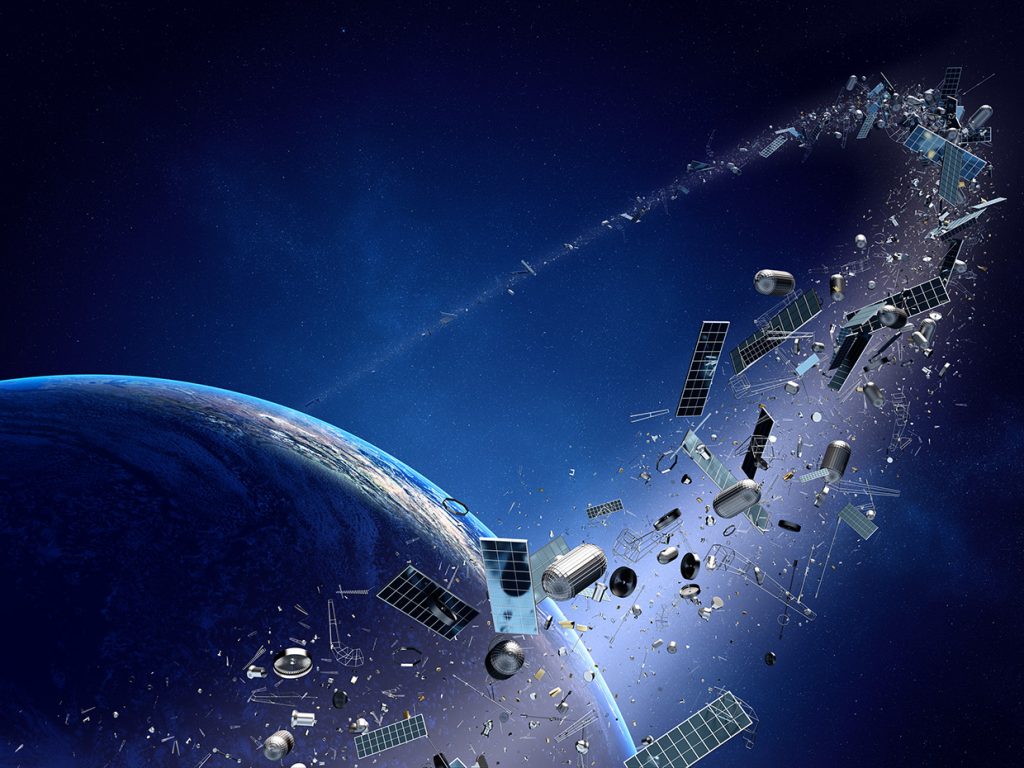

The Earth is engulfed in a cloud of debris, which consists of non-functional satellites and fragments arising from collisions, such as tiny screws and bolts traveling at such a high speed that they could cause massive damage to functioning satellites. It applies to objects greater than five to ten centimeters in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and thirty centimeters to one meter in Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO) (GEO).

The UNCOPUOS Science and Technical (S&T) Subcommittee’s 1996-98 multi-year work plan included the publication of the Technical Report on Space Debris in 1999. For the sake of a shared understanding of the word “space debris,” it reports the following concept introduced at the 32nd session of the S&T Subcommittee.

Space debris is defined as all manmade objects, including their fragments and pieces, in-earth orbit or re-entering the dense layers of the atmosphere that are nonfunctional with no fair hope of being able to resume their intended functions or any other functions for which they are or can be authorized, regardless of whether their owners can be identified.

Going by this definition of space debris, the decommissioned Russian satellite, Cosmos 2251, would, therefore, be nothing but space debris.

Why is there a need for International Legal Framework for Space Debris?

From a scientific, legal, and policy standpoint, the value of outer space sustainability as the sum of initiatives ensuring that the outer space environment is maintained for current and future generations has gained international attention. Given the dangers presented by the growing amount of space debris to some of the most heavily used orbital regions in near-Earth space, proper consideration of instruments aimed at space debris reduction and remediation is a vital tool for ensuring the feasibility of space operations in the future. Studies of the orbital evolution of space debris, on the other hand, indicate that implementing only mitigation steps would not be enough to ensure future access and usability of space.

Thus, space debris remediation (SDR) will play a crucial role in the sustainability of outer space and must become an integral part of the legal framework regulating its use. The Kessler syndrome was one of the most common theories suggested by NASA scientist Donald J. Kessler in 1978. The Kessler syndrome, also known as the Kessler effect, occurs when a high density of Low Earth Orbit (LEO) objects creates a cascading effect in which each collision produces space junk, increasing the probability of future collisions and debris. Excess space debris may have the unintended effect of making space operations and satellite use impractical for decades. Space debris can be created by any satellite, space probe, or manned mission. If the number of satellites in orbit increases, the Kessler syndrome becomes more likely. LEOs are the most popular manned and unmanned spacecraft.

The Legal Framework

The Liability Convention of 1972, the Moon Agreement of 1979, the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the Rescue Agreement of 1968, and the Registration Convention of 1975 are all relevant legal frameworks for outer space operations. The Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967, also referred to as the Constitution of Space Law because it entails the fundamental principles of space operations, is the most important of them all.

There are three articles that are pertinent to address the debris related issues i.e.

- Article VI of OST, which declares that States Parties to the Treaty shall bear international responsibility for national activities in outer space.

- Article VII of OST, which declares that State Party from whose territory or facility an object is launched, is internationally liable for damage to another State Party to the Treaty

- Article IX of OST, which prescribes that the launching state should take ‘appropriate measures’ in case it believes that their space exploration will lead to ‘harmful contamination of outer space.

However, there are no basic guidelines that show how a high level of treatment can be maintained when dealing with activities carried out by other states. As a consequence, while the current legal framework offers a framework for cooperation among various participants in outer space, there is still a lack of specific instruments that will help ensure the framework’s long-term viability. The existing legal structure neither prohibits the formation of space debris nor requires states and their space actors to remove debris that has accumulated in orbit. The majority of mitigation initiatives are either voluntary or non-binding, and some states have only partially implemented them in their domestic space law system...

On the 10th of February 2009, a major collision between an American and a Russian satellite occurred, resulting in thousands of untraceable fragments of various sizes roaming around with the constant danger of colliding with active satellites or interfering with their transmissions. The topic of space debris is a major one, as Matthew J. Kleiman, a professor at Boston University, correctly pointed out, since if enough debris accumulates, it would be nearly impossible to operate spacecraft in Earth orbit.

Legal Issues pertaining to Space Debris

The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 is the Magna Carta of space law. However, its provisions are far too general to effectively address the complicated issues of space pollution. Despite decades of attempts to describe the term space debris, no international agreement has been reached. Space debris is any man-made object that is either:

- Earth-orbiting and non-functional with no fair intention of assuming or resuming its intended function; or

- Re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere.

This term includes spacecraft fragments and component pieces, as well as decommissioned or failed spacecraft and spent booster upper stages. Cosmos 2251, a decommissioned Russian satellite, will thus be considered space debris. The Outer Space Treaty offers minimal guidance as to the mitigation of space debris at the State level, with much interpretation left to lawyers. For example, Article IX provides that State Parties to the Outer Space Treaty – shall conduct all their activities in outer space… with due regard to the corresponding interests of all other State Parties to the Treaty.

With some stretching and understanding, this can be used to obligate State Parties to prevent the formation of space debris, minimize it, and even eliminate it, allowing all States to engage in the exploration and use of space with minimal risk of debris.

The next sentence of Article IX specifies that outer space research and exploration shall be performed “so as to prevent their harmful contamination,” and that States Parties “shall adopt suitable measures for this purpose.” The article does not explain what constitutes “harmful pollution” or what constitutes “effective steps.” The term “harmful pollution” is commonly used to refer to biological or radioactive contamination, which is not the case for space debris.

Article IX also provides for an international consultation mechanism. If a State suspects that an action planned by it or its citizens would “possibly harmfully interfere” with the activities of another State, it must check with that state first. If a State Party suspects that an operation planned by another State would cause it potentially harmful interference, it can also request consultations. However, describing the presence or development of space debris as a potential “anticipated” operation is difficult. The provisions often fail to mention ongoing or completed operations, as well as the question of current space debris.

ESA lost contact with Envisat, the world’s largest nonmilitary earth observation satellite, on April 8, 2012. It is currently drifting uncontrollably in a sun-synchronous polar orbit, and the US Joint Space Operations Centre is tracking it. It is predicted that it would take 150 years for it to decay naturally by atmospheric drag, based on the scale of its orbit and area-to-mass ratio. During this time, there is also a chance of colliding with other orbital debris. Surprisingly, the issue that arises, in this case, is whether Envisat can be classified as “space debris.” It is otherwise an intact satellite that is drifting uncontrollably and is no longer maneuverable due to a lack of communications. If technical advancements allow it to re-establish relations with it, it can be re-commissioned as a “space object” and no longer be considered “space debris.”

Conclusion and Suggestions

More than 20,000 bits of debris larger than a tennis ball are traveling at 17,500 mph, which is around fifteen times the speed of a bullet shot. As a result, even a small piece of orbital debris may kill a spacecraft or satellite. Space debris is a pressing concern and a global issue for space activities. Although the dispute between the use and security of outer space, which has resulted in current patterns of accelerated and irreversible growth of space debris, is a serious issue, the legal response to date has been ineffective in terms of establishing binding rules for space debris mitigation and remediation. Real, a solution to such a complex problem cannot be developed solely by regulatory means; it also necessitates technological, financial, and political approaches that, when combined with an appropriate legal framework, can resonate with the dimensions of orbital space debris contamination. The problem’s importance cannot be overstated, and immediate action is essential for the use of near-Earth space.

Nonbinding legislation and efforts can play a significant role in space debris reduction, even if the law lags behind technical progress. They can also act as a foundation for the formation of binding laws. This trend holds true for space debris cleanup, which must be incorporated into the legal structure for extraterrestrial activities. The challenges for remediation seem to be at least as numerous as those for mitigation, but given the urgency of ensuring that the long-term use of space is not hampered irreversibly, the development of appropriate SDR mechanisms at the international and national levels should not be delayed, as they will define the future of the outer space environment and the viability of space activities.

Editor’s Note

The author discusses an important contemporary issue of pollution in space. The article discusses the issue in terms of the action taken against such pollution. Various regulations/conventions are discussed while stating that an effective solution lies in varied approaches across all fields of science and technology and not just law and policy.