Introduction

The desire of keeping something prudent forever is natural in human beings, as everyone likes to opt for long term benefits. But isn’t it against the law of nature that states “nothing is permanent in this world”? Perpetuity is simply ‘indefinitely long period’. In the field of law, this term is mainly dealt under property laws. It’s the right of an individual to transfer his or her property to the upcoming generations or to anyone else. The problem arises when such transfers are made in a way that makes them inalienable for an indefinite period. Such disposition is called transfer in perpetuity.

People, while worrying about their duty towards their ‘वंशावली’, forget about the right of their वंशावली regarding the property. Also, they become ignorant towards the importance of the frequent flow of property from one hand to another. They try to safeguard their property so that their successors would get its benefits. But what if they need it any other way apart from what their great grandfather have thought of and made the property inalienable?

It is illogical to imagine a dead person below the grave controlling properties above his grave.

Sir D. Mulla

This is more like giving food to someone but just to smell it and not eat it. There should not be any such transfer that will hinder the free and active circulation of property for the purpose of trade and commerce and also for the betterment of the property itself. It is a basic rule of ‘transfer of property act’ that one must enjoy the property absolutely during his lifetime. The person should not be deprived of enjoying his property in any possible manner.

How does the Perpetuity arise and what are the weapons to prevent it?

Perpetuity may arise in two ways; either by snatching the power of alienation from the transferor or by creating future remote interest. The first one is prevented by Section 10 of ‘Transfer of Property Act’ (TOPA), and the second one is prevented by Section 14 of TOPA. Before getting into these two sections, we need to get an overview of TOPA and it’s few basic sections, so as to simplify our understanding of these sections in the practical world. Transfer of Property Act, 1882 is an act that lays down the rules and regulations that governs the transfer of property from one person to another in India. It lays down the condition that makes the transfer complete as well as valid, the conditions that make a transfer void and also the conditions that qualify as an exception to the act.

Sec. 5 of TOPA has conditions for an act to be defined as a transfer. Following are the Conditions:-

- A living person must convey property. This section itself defines a living person including; company, association, or a body of individual whether it has been incorporated or not.

- The conveyance of the property can be carried out in both present and future. This conveyance can be carried out between one or more living persons, including himself.

Sec. 6 of TOPA enlists the exception that cannot be transferred as a property. Except for them, everything else can be a property and can be transferred. Sec. 7 explains who is competent to transfer. Sec. 13 has an important status as it talks about an unborn child as a transferee of any property. We will talk about this section later on in the article.

Legal Points

Now, let us go through the two most important weapons we have to prevent perpetuity to arise that we discussed above. Section 10 of TOPA speaks about any condition kept while transferring the property that absolutely restrains the transferee from disposing of the interest is void. This simply means if any such condition is created that imposes restriction over transferee regarding the selling of property as to whom he can sell it or regarding the price on which he can sell it, or how to utilize the consideration or for what purpose he can sell the property or use it or the time when he can transfer, any such condition will be void.

For example, if A sells his property to B with a condition that he cannot sell this property during his lifetime, this condition is void, the same has happened in Kosher V. Kosher. It is important to understand that such a transfer is legitimized with mutual consent of both the parties but, the fulfilment is not binding on the transferee. The principle governing this rule is that of justice equity and good conscience. This section talks about absolute restrain and remains silent about partial restrain. For example, where the restrain is in such a way that it does not take away the power of alienation absolutely but only restricts it to some extent, then that restrain will not be void.

It will also depend on the fact and substance of the case as in the case of Mata Prasad V. Nageshwar Sahai (1927) where there was a dispute regarding succession between nephew and widow. A compromise was formed where the possession of the property was given to the widow while the title was given to nephew and a condition was made that he cannot sell the property during the lifetime of the widow. The condition and compromise were thus held valid.

Thus, it becomes absolutely important to understand the difference between partial and absolute restrain. Selling property only to a particular class of person is not an absolute restrain but selling property only to a particular person is an absolute restrain.

In the case of Mahamudali Majumdar v. Brikondar Nath, the condition was that the transferee can only sell the property to the family members of the transferor, though this is a partial restrain, the court held that the person who himself is selling the property to an outsider cannot bind the latter to sell property only to the family members of the transferor and thus the condition was held void. The main objective of creating this section was to prevent the transferor from keeping any arbitrary condition just for his own interest. The rule of absolute restrain is void and is founded on the principle of the public policy allowing free circulation and disposition of property. There are 2 exceptions of this section:

- Lease is a transfer of property wherein the lessee only has the right of enjoyment, while the ownership still lies with the lessor. In this case, condition imposing restrictions (for the benefit of the lessor or those claiming under him) are valid. As in the case, Raja JagatRanvir V. Bagriden a condition in the lessee shall not sublet or assign was held to be valid.

- Married Woman: When the property is to be transferred to a married woman, who is not a Hindu, Mohammedan or Buddhist, then the condition restricting alienating can be valid.

Rights of an Unborn Child

Let us talk about the most complicated and equally important sections of TOPA. Yes, I am talking about Sec. 13 and 14. First, we will discuss how Sec. 13 gives a right to an unborn person to get the property from its well-wisher and how these two sections prevent a person from creating any hindrance in the frequent disposition of property that is healthy for both the state as well as the property itself.

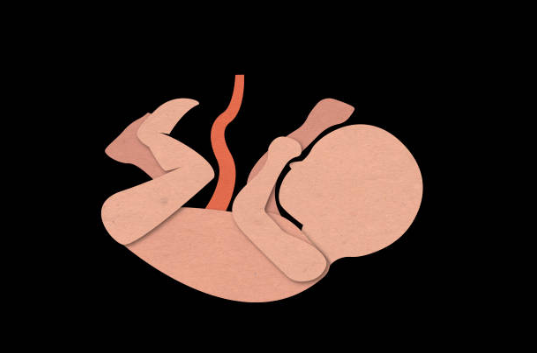

An unborn child is someone who is not in existence during the time of transfer was made. A child in the womb will not be considered as an unborn child. Sec. 13 states that “where on a transfer of property, an interest therein is created for the benefit of a person not in existence at the date of transfer, subject to a prior interest created for the benefit of such person shall not take effect unless it extends to the whole of the remaining interest of the transfer in the property”. From the language of Sec. 13, few things are very clear that can be understood as the prerequisite conditions for a valid transfer of property to an unborn person:

- As it is clear from Sec. 5 that property is transferred between two living people, so it cannot be transferred directly to an unborn person. And thus the person who wants to transfer property for the benefit of an unborn person should first make a life estate in favour of a living person.

- An absolute estate needs to be created in favour of that unborn child. The person who gets the life estate of the property would hold the possession of the property, and enjoyment of the property. On the birth of that unborn child, the title of the property gets immediately transferred to that child but he will get the possession only on the death of the life estate holder.

Illustration: A wants to give his property to B’s unborn child so he makes a life estate of the property in favour of B and an absolute estate in favour of B’s unborn child which he will get after his birth. Now, this transfer is valid.

There is one very important case that puts forth wider interpretation of Sec. 13 Bajrang Bahadur Singh V. Thakurdin Bhakhtrey Kuer. The Supreme Court of India, in this case, held that no interest can be created in favour of an unborn person but when gift is made to a class or series of person, some are in existence and some are non-existent, but it doesn’t fail completely. It is valid with respect to those who are in existence till the time of testator’s death and is invalid with respect to the rest.

Now it’s time to go through the antidote of that ‘पीढी’ concept where people make remote interest in favour of their upcoming generation without even thinking about the negative side of such an eccentric idea. If that primitive concept of ‘only the royal child will be the heir of the throne’ would have continued, it would have made almost all properties static. This section is also based on the principle of public policy and thus Sec. 14 plays a very vital role in preserving properties from being misused.

No transfer of property can operate to create an interest which is to take effect after the lifetime of one or more person living at the date of such transfer, and the minority of some person who shall be in existence at the expiration of that period, and to whom, if he attains full age, the interest created is to belong.

Section 14 of the Transfer of Property Act

The above-mentioned definition of the Section makes the following points very clear to us-

- Why this section is called ‘rule against perpetuity’ because it limits the maximum time period beyond which property cannot be transferred. And that MTP is equal to the date of transfer of property + lifetime of all the living person before the last interest holder + gestation period of the unborn beneficiary + age of majority of last beneficiary.

- The transfer should create an interest in favour of an unborn person and must be preceded by life or limited interest of a living person.

- The chain of transfer by each person will break after two generations and that unborn beneficiary will get the absolute interest.

- The unborn beneficiary must come into existence before the death of the last preceding living person. Thus by limiting time period and by making transfer absolute to an unborn as mandatory prevents perpetuity.

Exceptions to the Rule against Perpetuity

- Sec. 18 of TOPA states that when a transfer is made in the favour of public viz. advancement of knowledge, religion, commerce, health, safety or any other object beneficial to mankind. Sec. 14 doesn’t apply here.

- Personal agreements that don’t create interest in the property.

- Renewal of lease agreements.

- Covenant of redemption of property under mortgage

- Charge created over the property, as this doesn’t amount to transfer in interest.

- Contract of pre-emption. The ‘Indian Succession Act’, 1925(ISA) regulates intestate and testamentary succession. Sec. 113, 114, 115 and 116 are contemplations of sec. 13, 14, 15 and 16 of TOPA as the transfer of property also takes place through ISA. Before TOPA, any property given as a gift to an unborn was void under Hindu and Muslim law. Though the position in Muslim law is still same but for Hindus, it got modified a lot since TOPA came into play.

Conclusion

People always like to keep their property in their families for generations. That creates a big problem as the property remain no longer available for the benefit of society and also the property gets negatively affected. It is also a very unhealthy transaction for trade and commerce as the frequent flow of property gets hindered. It is the primary duty of law to check on such unhealthy practices and to stop it. To avoid perpetuity, Sections 10, 13 and 14 make mandatory provisions to prevent it. The sections are founded on the principle of public policy. Where one section limits the time period to keep the property in one hand, the other provides the right to transfer property for the interest of an unborn. Thus these are weapons that work as a full stop on a never-ending concept of perpetuity.